Human testimony in the age of AI

Why public decisions need sourced quotes, not just AI answers

I recently used an LLM to explore epistemology, basically how we know what we know, and ended up reading Jennifer Nagel’s Knowledge: A Very Short Introduction. One point that stuck with me: we separate knowledge from belief not only through perception and reasoning, but through other people’s testimony.

We rarely notice how much of daily life runs on trust. From learning language as children to checking the capital of a country on Wikipedia, we rely on collective testimony. We trust those systems more when they include accountability mechanisms: revision history, citations, and a clear way to contest errors.

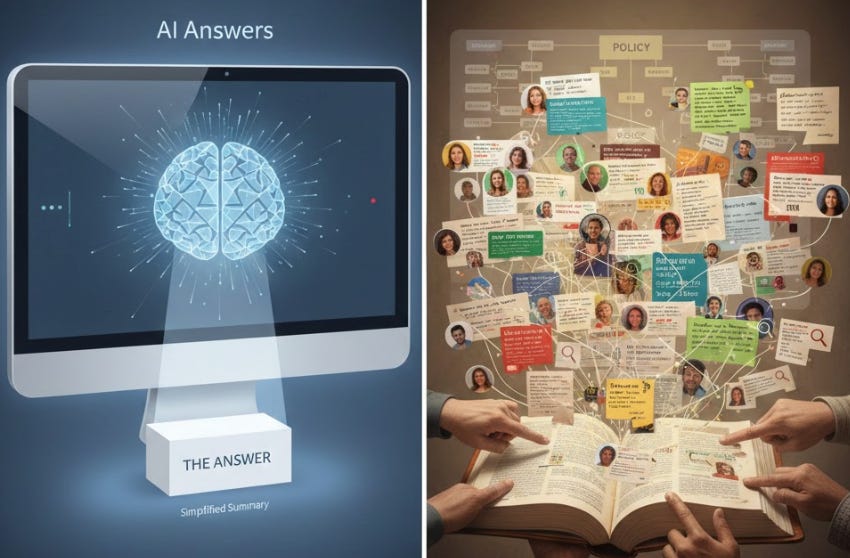

As LLMs improve and offer citations, the temptation to trust them grows. However, most research-assistant interfaces optimize for a single “clean” answer. In governance, this is a liability: it obscures minority views, edge cases, and the specific conditions under which a claim stops holding.

In epistemology, testimony can fail when there are “defeaters,” meaning concrete reasons to doubt it (for example, someone claiming it’s snowing in Madrid in July). In high-stakes policy, a clean summary can be dangerous if it hides those reasons: counterarguments, conflicting evidence, or “this only holds if…” conditions. We need interfaces that make doubts and conditions easy to spot, especially when more work relies on a small number of model providers and platforms.

We’re building YouCongress to surface counterarguments, uncertainties, and the conditions that make claims fail. Today it is a growing library of sourced quotes on policy questions, each labeled by stance and linked to the original source with timestamps so readers can check provenance. The goal is not a single “truth”, but an inspectable record of disagreement that decision-makers can audit before committing.

Concretely: you can explore a policy question and browse primary-source quotes, labeled by stance (For, Abstain, Against). This structured dataset is the raw material we need to build decision maps that surface the main arguments, counterarguments, and uncertainties.

Example decision map

Question: Should we restrict releasing open-weight models above a defined capability threshold to reduce catastrophic misuse?

Quotes and primary sources: see “Ban open source AI models capable of creating weapons of mass destruction (WMDs)” on YouCongress.

- Position: Restrict releases above a threshold

- Core argument: Once weights are public, safeguards become optional, and enforcement becomes substantially harder in practice. (Esvelt; Scharre)

- Technical risk: Determined users can often fine-tune around safety behaviors, so there may be no durable way to prevent harmful assistance once weights are widely available. (Adler)

- Policy Implication if restriction is adopted

Governance often shifts toward certification, liability, and sometimes export controls. Releasing weights is treated less like publishing code and more like distributing a hazardous capability. (Russell; Bengio; Hassabis)

- Key counterarguments and uncertainties to surface

- Monopoly and concentration risk: If we restrict open weights, do we unintentionally concentrate frontier capability in a few firms or governments, and is that outcome worse than the misuse risk we’re trying to reduce? (Yann LeCun; Andrew Ng)

- Enforceability in a global, decentralized compute landscape: Even if one jurisdiction restricts releases, does that meaningfully reduce access, or does it just shift use to other countries and actors while reducing transparency at home? (Tal Feldman; Andrew Ng)

- Alternative mitigation pathways: If the core worry is bio/cyber misuse, are there more effective interventions than restricting weights? E.g., major investment in bio-defense, better screening, or response capacity. (Marc Andreessen)

- Why This Matters

If institutions require strong assurances that a model stays within safety bounds, open weights can make those assurances difficult to guarantee in practice, especially once models can be fine-tuned and redistributed widely (Alexander; Sutskever; Hinton; Yudkowsky).

The point isn’t to win the argument, but to make counterarguments and uncertainties legible before a decision hardens into policy.